Automation and Machine Learning for Grid Power-Use Minimization in Sustainable Residential Architecture

Abstract

text

Table of Contents

- Glossary

- 1. Introduction

- 2. Literature Review

- 3. Methods

- 4. Results

- 5. Discussion

- 6. Summary and Conclusions

- Acknowledgements

- Appendices

- References

Version/Revision History:

| Version/Revision | Date Published | Details |

|---|---|---|

| V00, Rev.01 | 2021-11-25 | Initial Draft |

| V01, Rev.00 | 2021-12-27 | Midterm Submission |

Glossary

1. Introduction

This study theoretically examines the feasibility of achieving greater energy savings in sustainable residential architecture using automation and machine learning.

Both the smart-home and low-energy/sustainable-home industries are well-established and continue to grow. While many engineers work on the problem of energy storage, addressing energy consumption can yield results that are just as impactful.

Achieving higher efficiencies in homes that are already designed to save energy may be possible or even generally applicable. It is the objective of this study to form a conclusion about how well this can be accomplished using an automation and machine learning approach.

Consider a passive solar home (similar to the one shown in the figure below). The building in the image features an 80-foot-wide by 7-foot-high, south-facing wall of windows designed to allow solar radiation to pass into the home and heat up the concrete floor. The floor acts as a thermal heat store and dissipates heat back into the home over the following days. All passive solar homes share some version of this design.

Desirable amounts of low-energy-consumption heating and cooling are achieved in the pictured home by manually opening and closing blinds and windows to alter radiative and convective heat transfer into and out of the house. Although it reduces the amount of grid power used for heating and cooling, opening and closing the blinds and windows is repetitive and labour-intensive. This makes it an excellent candidate for automation.

Deciding when to, and how much to open the blinds and windows is not trivial. A great deal of knowledge about thermal behaviour or experience about how the temperature in the home will change is needed to make the right decision. This decision-making process may be well addressed using machine learning—a data-driven method that removes the need for creating a definitive mathematical model of the system being controlled.

In this study,

- a theoretical, nodal thermal model is created to simulate the passive solar home introduced above,

- a theoretical control system is defined as a substitute for real-world automation of blinds and windows,

- a machine learning controller is built and implemented, and

- the results achieved by the control system are evaluated and discussed.

2. Literature Review

Trade-offs between performance and resource expenditure have always been a driving force for innovation, and building energy is not exempt. The contradiction between indoor environmental quality (IEQ) and energy savings is well-understood and has been the focus of many researchers over recent decades. 1

Indoor environmental quality encompasses many factors including temperature, humidity, light, and sound control. HVAC is an important and non-trivial portion of indoor environment quality (IEQ) control problems because of the amount of energy it requires, the influence of user setpoints, thermal mass, Spatio-temporal variability. 1

Energy consumption depends on the climate, but statistics show that heating and cooling systems account for a substantial amount of energy consumption on a national level. In commercial buildings, the subsystems with the largest energy consumption are HVAC and lighting. 1 In the UK, the estimated energy consumption for these two systems is 40% of all commercial building energy consumption. 2 And in Canada, where the climate is colder on average, that figure is 70%. 3

Innovators have addressed the IEQ-energy consumption contradiction in myriad ways. Applications of automation and control applications targeted at mitigating this trade-off can be classified as rule-based, model-based, and model-free methods: 41

- Rule-Based Methods – Rule-based control schemes are effectively a set of control rules defined by the intuition of an informed facility manager. 41 Zhang et al. 1 say that the research shows that this type of control scheme can significantly reduce the amount of energy consumed by an HVAC system. 5 However, a significant drawback is the dependency on the quality of results on the quality of the control rules. 1

- Model-Based Methods – Model-based methods make use of physics- or data-driven models that effectively describe and predict the behaviour of the dynamic system. 4 Low-order heat-transfer functions have been used to control buildings with some success; 67 but, proper identification of the high-order heat-transfer functions that accurately characterizes a real-world situation can be quite difficult. 1

- Model-Free Methods – Model-free methods bypass the need for intuition- or data-driven models by learning control policies through (trial and error) interactions with the systems they control. 4 Despite the broad application of reinforcement-learning (RL) models to building system control in recent years, their relative performance, stability, and convergence speed have not been well-studied. 1

2.1 Applicability of Automation & Machine Learning

The most recent automation and control approach with, perhaps, the greatest potential has been machine learning. Howard and Gugger, in their 2020 publication Deep Learning for Coders with fastai & PyTorch 8, outline several inherent advantages and limitations of machine learning:

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

| Black-box-like ability to generate accurate results for a set of inputs without any instruction about how to do it. | Subject to biases and other issues that arise with statistical and probabilistic methods. |

These are discussed in more detail in Appendix B.

Model-free, or “machine learning” methods have been a recent approach to building system control. 9 Three reinforcement learning types are commonly used: 1

- Q-learning (value-based) – Q-learning algorithms “update action values (i.e., Q-values) for each state based on the observation.” 1

- Actuator Critic – Actuator critic algorithms “learn the control policy as well as the Q-values to update the control policy.” 1

- Policy Gradient – Policy gradient algorithms “are… the least sample efficient, yet are more stable than other RL algorithms.” 1 Of the 77 studies reviewed in Reinforcement learning for building controls: The opportunities and challenges, Wang and Hong 9 found that 75% used value-based algorithms.

2.2 Previous Work on this Topic

In their 2021 paper, On the Joint Control of Multiple Building Systems with Reinforcement Learning, Zhang et al. 1 demonstrate that “11% and 31.8% more energy can be saved respectively in heating and cooling seasons over rule-based baselines that control the same [comercial] buildings.” The contributions that the authors 1 make regarding,

- state-of-the-art reinforcement learning control schemes,

- the contradictions between energy consumption, thermal comfort, and visual comfort, and

- the performance of the proposed methods in joint control of energy systems when occupancy behaviour is known,

far exceed the scope of this undergraduate-level feasibility study; however, their paper is recommended as further reading, particularly for joint-control, commercial-building applications of the same automation and machine learning approach to energy savings proposed here for low-energy consumption homes.

3. Methods

The method of this feasibility study is theoretical. No real-world testing is done. Instead, a real-world situation—the passive solar home discussed in the introduction—is distilled down to a set of parameters that all influence the amount of electrical power consumed for heating or cooling the home. The resulting shoe-box model is simulated in EnergyPlus, a nodal building energy simulation engine. And, the outputs are recorded for arbitrary sets of these parameters. The resulting dataset labelled, and will serve the purposes of training, verifying, and testing a machine learning control program.

Based on an understanding of machine learning and its applicability, as well as previous work done in the field of building energy, an appropriate architecture is chosen. This architecture is then trained, verified, and tested using the dataset generated in Energy Plus.

The energy savings achieved with the machine learning control application are compared to an analogous situation where no control application is used, and the results are discussed.

3.1 Control System

For this study, the process of defining the whole control system is one of simplifying a real-world scenario, while preserving all essential aspects. To do this, the objectives of the control system are clearly stated, simplifying assumptions are made, and all critical parameters and dependencies are identified.

In the introduction, a passively-solar-heated home was discussed. This residential building is quite complex, so simplification is guided by the final objective of the whole control:

The final objective of the control system is to (1) achieve the user’s set point for indoor temperature with automated control of windows and blinds, while (2) minimizing the amount of power supplied to the heating system.

With this information, aspects such as thermal loads, an auxiliary solar water-heating system, internal geometry (eg. furniture), and humidity are ignored. All heat transfer into and out of the building influences temperature regardless if by conduction, convection, or radiation. Convection is controlled by opening and closing windows. Radiation is controlled by opening or closing blinds. And, the HVAC makes up for changes toward the user’s setpoint that cannot be achieved otherwise. Each action, whether it be opening or closing windows or blinds, or heating or cooling with the HVAC system will affect the interior temperature of the home. Because of these dependencies, understanding what happens to all of these parameters when something inside the building is changed is critical:

- Constraints

- temperature (user setpoint)

- Control (Independent) Parameters

- % closed (window 1)

- % closed (window 2)

- % blinded (window 1)

- % blinded (window 2)

- Dependent Parameters

- temperature (inside at the elevation of window 1)

- temperature (inside at the elevation of window 2)

- Invariable Parameters

- temperature (outside)

- sun angle

- sun intensity

- Parameter to be Minimizes

- heat gain (due to the H-VAC system)

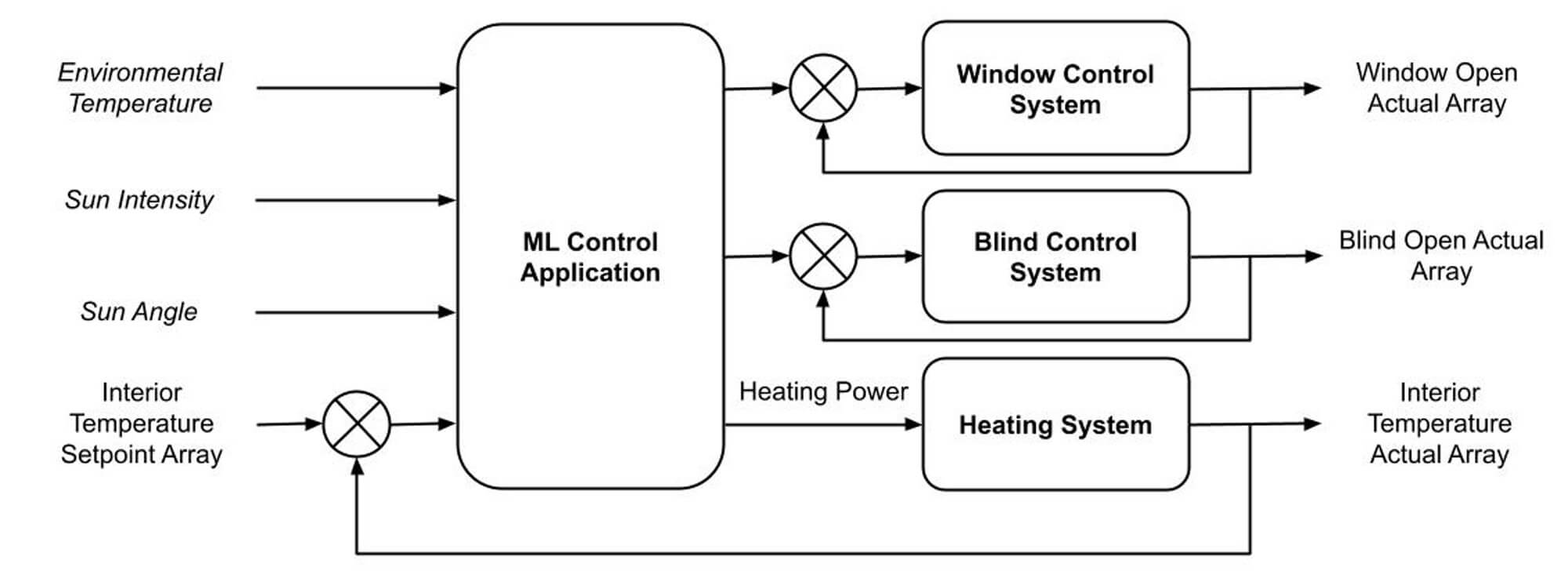

A block diagram representation of the control system can help visualize the role these parameters play on the system as a whole:

The machine learning (ML) control application is given a set of inputs about the outdoor conditions and an error rate indicating the difference between desired and actual indoor conditions and is tasked with the objective outlined above. Its outputs are a set of commands for the amount to open or close windows and blinds as well as an amount of power sent to a heating system.

3.2 Thermal Model

Historically, both experimental apparatuses and computer-driven simulations have been used for the validation of scientific theses, particularly in the field of engineering.

In conversation, Evins 10, a building-energy researcher and instructor at the University of Victoria, explained that data has been a stumbling block in the building-energy research field. Often, data sets are available, but not enough information about where they came from is available to make these sets useful for all applications. Moreover, machine learning is inherently heavily data-dependent. In certain applications, like thermo- and fluid-dynamics, more data can be obtained from computer-driven simulations than analogous experimental apparatus’ because of the absence of spatial sensor constraints. Hence, a computer-driven simulation model is used for this study. Evins 10 suggests using EnergyPlus, a nodal building-energy simulator for constructing a computer-driven thermal.

Even with an EnergyPlus model that is simple, the impact of windows and blinds on internal temperature can be studied effectively. A simulation that reflects the simplified control system outlined in the previous subsection (3.1) requires only the fundamental geometry, an HVAC system, and a set of windows and blinds. This can be simplified further to a “shoe-box” model consisting of just a two-story box with an HVAC system and windows on the first and second floors.

The process of constructing and running this simulation in EnergyPlus is discussed in depth in Appendix A.

3.3 Neural Network Structure

Building a Neural Network

3.4 Neural Network Training

Training the Neural Network

3.5 “Prediction” Validation

Validating the “Predictions”

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Summary and Conclusions

Acknowledgements

Appendices

References

-

Zhang et at., 2021: On the Joint Control of Multiple Building Systems with Reinforcement Learning ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7 ↩8 ↩9 ↩10 ↩11 ↩12 ↩13 ↩14 ↩15

-

U.S. Energy Information Administration, 2020: Energy Use Data Handbook ↩

-

Natural Resources Canada, 2019: Energy Use Data Handbook ↩

-

Ding et at., 2019: OCTOPUS: Deep Reinforcement Learning for Holistic Smart Building Control ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4

-

Ardakanian et at., 2018: Non-intrusive occupancy monitoring for energy conservation in commercial buildings ↩

-

Goyal et at., 2011: Identification of multi-zone building thermal interaction model from data ↩

-

Zhou et at., 2017: Quantitative Comparison of data-driven and physics-based models for commercial building HVAC systems ↩

-

Howard and Gugger, 2021: Deep Learning for Coders with fastai & PyTorch ↩

-

Wang and Hong, 2020: Reinforcement learning for building controls: The opportunities and challenges ↩ ↩2